Photo of The African American Flat Rock community taken about 1900

The Emancipation Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln

On January 1st, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This proclamation promised freedom to all enslaved people living in areas that rebelled against the United States of America. The Northern Union Army had to defeat the Southern Confederate Army in the Civil War to fulfill this promise. Over two years later, on April 9th, 1865, Lincoln's promise was upheld when the Union Army won the Civil War. Enslaved people were finally able to begin their lives as free citizens of America.

(Herline & Hensel. Abraham Lincoln / Herline & Hensel, lith. 632 Chestnut St., Phila. [Philadelphia: published by joseph hoover, 108 sth. 8th St., between 1860 and 1865] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2006677676/>)

Civil War: The Battle of Atlanta 1864

A Secondary Source Narrative from Union Soldiers of the Thirty-Third Mass. Infantry Regiment:

In November 1864, Atlanta was smoldering, with most of the buildings burnt to piles of rubbish. The air was filled with floating embers, and the smell of smoke filled the soldiers’ lungs. They picked up what little belongings they had and began to head east. Excited that they defeated the Confederate Army, the roaring flames were a sobering reminder that it was at a painful cost. The occasional explosions of the burning buildings still startled some of the walking soldiers while others had grown accustomed to the loud bangs and explosions that their bodies barely flinched at the loud noises. The death and destruction that the marching soldiers saw with their eyes stayed in their minds forever.

About 26,000 marching soldiers headed East from Atlanta. A band in the distance began to play during the march, and many men joined in to sing the chorus, “Glory, Glory, hallelujah.” The regiment followed under the guide of General Cogswell along the mangled and burning steel that was once a bustling railroad track. The track ran in a line for miles and appeared as a burning stream of fire. They marched directly through Flat Rock as they crossed Snow Finger Creek and continued through Lithonia and Conyers.

The countryside was peppered with newly freed people that ventured out of their cabins, farms, and plantations to meet the singing soldiers and what seemed to the former slaves as the day of Jubilee. One newly freed man said he had been waiting for this ‘Angel of the Lord since he was knee high’ when he referred to Sherman. An Old Auntie exclaimed, “I’m so blessed that there are so many of God’s critters in the world.” At every crossroad and plantation, more freed people joined the crowds singing with the bands playing their instruments. It looked as if some of the people running to celebrate freedom were carrying everything they owned with the help of mules and old horses pulling rickety old carts trying to join the wagon train.

In Freedom: Emmaline Heard from the Federal Writers’ Project Interview

When the owners of Emmaline’s family learned that the enslaved people were free, they offered Emmaline’s father and mother a house, mule, hog, and cow if they would stay and work on the plantation. Emmaline’s parents thought they would have a better living situation somewhere else, so they decided to work at a different plantation in a neighboring county.

When Emmaline was old enough to take care of herself some years after freedom, she moved to Atlanta. She lived in Atlanta ever since and was an older woman at the time of her Federal Writers’ Project interview in 1937. At that time, she was being cared for by her granddaughter and son.

In Freedom: Harriett Hill from the Federal Writers’ Project Interview

Harriett Hill lived at the Lyon’s farm until Jim George sold her to Sam Broadnax. When freedom came after the Civil War, Harriett stayed on the Broadnax farm. She remembered that freedom came in the springtime. Mr. Broadnax convinced some of the formerly enslaved people to stay and help finish harvesting the crops. They got paid a tenth of the money that the crop sold for at Christmastime.

After they were paid at Christmas, the landowner said he was going to keep Harriett and sell her for a bounty. After Harriett learned this, she ran far away from the farm with a girl named Kitty. Harriett and Kitty ran through a field to Conyers, Georgia. Kitty left Harriett at a railroad track. Harriett followed the tracks all the way to Lithonia, Georgia. She remembered walking all night.

Not long after Kitty left, Harriett’s brother came riding up in a wagon. Although she did not know it was her brother, he recognized her immediately. He took Harriett to Mr. Jake Chupp’s place in Lithonia, where she was able to eat a good meal.

After she ate, her brother took her to see her mother. She had not seen her since she was three years old, but her mother remembered her.

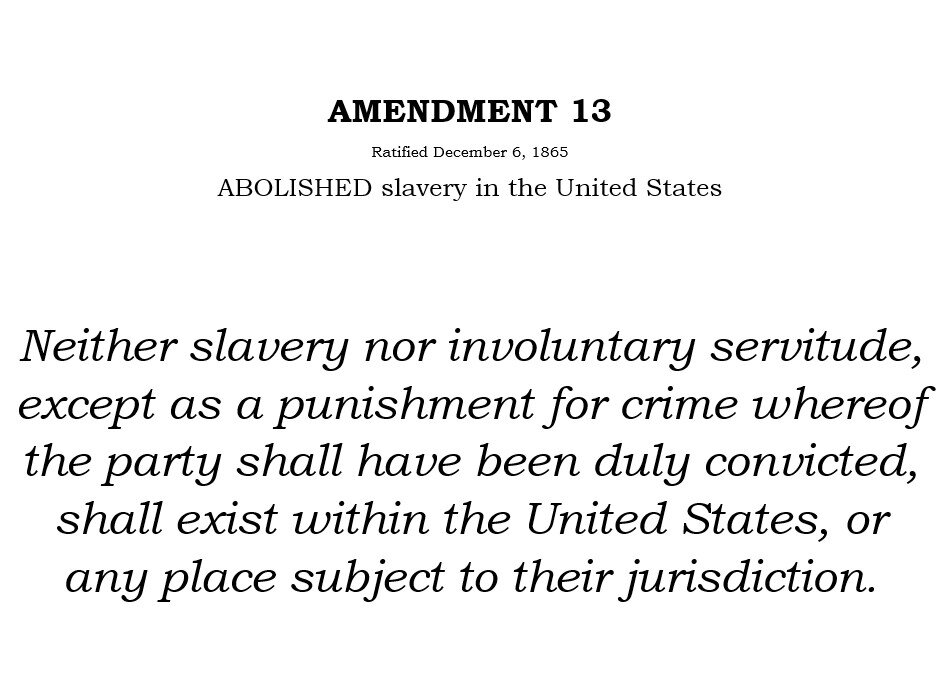

In 1863, President Lincoln created a program for the reconstruction of the United States. The end of the Civil War brought many changes. The Northern and Southern states were integrated again, and slavery was ended. The Thirteenth Amendment of 1865 officially ended the practice of slavery. The government also promised every ex-slave family “40 acres and a mule”. Even though that promise was not honored, white Southerners became worried about the economy and generally fearful about the future. This fear led to the Black Codes of 1865-1866. The Black Codes limited the rights of newly freed Black people. For example, marriage between Black and white people was illegal in many states. The Black Codes were used to control Black people by requiring them to follow strict rules. They had to work all day, six days a week. Also, whites were allowed to whip Black people under the age of 18. Black people were not allowed to own guns or sell crops without their white employers' permission. Northern states protested the Black Codes and claimed that Southerners were using the Black Codes to continue the practice of slavery.

The government responded to the Black Codes by passing the 14th Amendment in 1868. This Amendment gave ex-slaves full citizenship in the United States and promised they would have “equal protection of the laws.” The Fifteenth Amendment of 1870 gave Black males the right to vote as long as they met certain requirements, like proof that they owned land. Southern states responded to this Amendment by issuing the Jim Crow laws in the 1890s. These laws required Black and white people to have separate public spaces. There were separate schools, hospitals, bathrooms, hotels, libraries, etc., for Blacks and whites. This separation of Blacks and whites, known as segregation, was practiced until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s-1960s. The Civil Rights Movement ended segregation and promised all United States citizens equal rights.

The Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution:

In Freedom: Archie George from the Federal Writers’ Project Interview

Archie George grew up after the Civil War. When he was young, he was a sharecropper in Lithonia, Georgia. The landowner furnished the seeds to plant, mules to plow, tools, and anything else they needed. At harvest time, they got half of the money earned.

Archie’s family always had plenty of food to eat. He always wanted a bicycle but never got one. He rode a mule instead. Archie only went to school for about two years. He never learned to write, but he could read a little. His sisters went to school a lot more than Archie. He mostly worked in the fields as a young man.

Flat Rock Community Members Buy Land

The Flat Rock African American community members began to buy land from former enslaving families in the area. It was difficult to find landowners that would sell the property to African Americans. In 1896, the land was purchased where the church, pictured above, was located. A few years later, the community purchased land for the schoolhouse. Eventually, community members were able to buy land to build houses and farm crops.

The Flat Rock Rural Schoolhouse Burned in the 1940s

The African American Flat Rock community overcame many challenges. It was difficult for them to purchase land and build a school. It was hard to maintain even after the land was purchased and the school was built. Around 1947, the Flat Rock rural schoolhouse was burned along with other African American churches and schools in the area.

Hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan were responsible for terrorizing and destroying the property of African Americans throughout this area of Georgia. Below are several historical newspaper articles that discuss the destruction of life and property in Flat Rock and other small African American communities. The newspaper articles date from 1919-1947. These articles provide just a few examples of the terror and threats that African American communities faced during the twentieth century.

When the Flat Rock rural schoolhouse was burned in 1947, the community did not stop going to school. The students met in a church building where they continued to study. The perseverance of the Flat Rock community members still rings in the stories told by them today, and it demonstrates hows the determination of this community to share the stories of their ancestors and preserve their history for future generations.

1919 The Chicago Defender Newspaper

1936 Atlanta Daily World Newspaper (African American Newspaper in Atlanta, Georgia)

1945 Atlanta Daily World Newspaper (African American Newspaper in Atlanta, Georgia)

1947 Chicago Defender Newspaper